Lynn Novick is, with Ken Burns, the director and producer of the ten-episode, eighteen-hour documentary THE VIETNAM WAR airing on PBS through September 28. The duo worked on the project for ten years, with Novick making multiple trips to Vietnam. In a phone interview, she discusses her work on the historical epic.

ASSIGNMENT X: How did you initially come to work with Ken Burns?

LYNN NOVICK: Ken and I have been working together since 1989. So I worked with him when he and Ric Burns were finishing up THE CIVIL WAR series, and they hired me to help finish up the project. And then I produced the BASEBALL series and JAZZ, and we’ve been co-directors on FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT, PROHIBITION, THE WAR – the Second World War series that we did. So we’ve been working together for almost thirty years.

AX: When you both direct, does that mean that you’re both going through the footage and both saying, “I think that we should use this and not that”?

NOVICK: That’s part of it. Ken and I have an incredible team of producers and editors and a cinematographer, and our [narration] writer, Geoff Ward, one of the most important people. Our job is to give them direction, oversee them. Then, when we have the material all collected, we [Novick and Burns] collaborate to shape the narrative that we want the film to be. But it’s a process. It starts at the beginning with a blank piece of paper, and ten years later, it’s a ten-part series. And there are many different pieces along the way, and a lot of things that have to get done, some of which we do, and a lot of which we also have delegated to some incredibly talented people.

AX: Are you one of the people conducting the interviews?

NOVICK: Yes. In the case of this project, I conducted most of the interviews.

AX: Did you go to Vietnam to interview the North and South Vietnamese participants?

NOVICK: Yes, I just came back yesterday from my fourth trip to Vietnam.

AX: THE VIETNAM WAR documentary is completed, so what was this latest trip to Vietnam for?

NOVICK: It was to do something similar to what we’ve been doing here, which is to show clips, and to in this case, also to see the people who are in the film, and thank them and show them some of the sections of the film that they are in. We’ve had the whole film translated into Vietnamese, so we couldn’t do this trip until we had that done. So we were able to share with them not just their parts, but also some of the other sections of the film. It was an amazing trip.

AX: Has anybody had an unexpected reaction to the film?

NOVICK: That would presuppose we’d have an expectation for what their reactions might be, so I think generally the reactions have been very similar, there and here, among everybody that we’ve been in touch with [who is] in the film. Many people who see the film realize that they only know their part of the war. [There were] other parts of the war that they didn’t know about. The Vietnamese didn’t know what was happening on the American home front, for example, or the White House. So there were a lot of [questions the Vietnamese had] – “Why did the Americans come to Vietnam? They didn’t really know that much about us. What was it like for American soldiers? What did they think of us?” And then, for the North Vietnamese, what did they think of the South Vietnamese, and vice-versa? There are a lot of examples of what is existentially the human condition. You can only see the world from where you are, and so the film gives [everyone] a chance to see their experiences filtered through many other lenses. And the thing that struck us again and again in Vietnam, but also here, is the sense of common humanity. The Vietnamese that we’ve shown the film to keep commenting on the authenticity and the verisimilitude of the film, and how much it humanized everybody on all sides. Americans say the same thing when they see it.

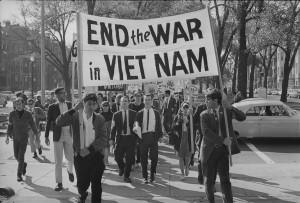

College students march against the war in Boston. October 16, 1965 from the Ken Burns documentary THE VIETNAM WAR | photo Courtesy of AP/Frank C. Curtin

AX: Was anyone upset?

NOVICK: I think that there are certainly many people that have experienced very traumatic events in the war and still have some scars around that. So there’s anger, there’s frustration, there’s pain, there’s loss, and some of it is directed toward the enemy, whoever their enemy was, or to their leaders, or the other side’s leaders. I think there’s a lot of unprocessed pain around this event on all sides.

AX: What did you learn while making this, if anything, that really surprised you?

NOVICK: I’m sure if you asked Ken that, he probably said, “Everything.” It’s what we really have been saying, because it’s a subject I think we both though we knew a fair amount about, but in fact, there were revelations large and small throughout this entire project. Conducting the interviews for the film surprised me every day, because of the [ways] that people choose to talk about such painful and difficult experiences, and choose to reveal themselves, sometimes to themselves and certainly to our camera, and ultimately to a lot of people who are going to see the film. So I’ve found surprising, and I’m sure Ken did, too, the sense of inner conflict that many people still feel, how raw and right below the surface their feelings and experiences and memories are of these events that happened fifty years ago. The big revelatory takeaways on a historical level for us have been having had the chance to read some of the Pentagon Papers, listen to the presidential audio recordings that we put into the film, coming to understand that there was never a time when our leadership really believed, had confidence that we could win the war, and yet kept on perpetuating it, and sometimes escalating it, even without any real sense that it would probably turn out well.

AX: Did you have to ruthlessly cut the material down to get it to be only eighteen hours?

NOVICK: Believe it or not, we did [laughs]. I know it sounds ridiculous, but we interviewed a hundred people for over two hours [each]. That’s two hundred hours right there of material. We collected 25,000 photographs and thousands of hours of footage. And then Geoff wrote the narration, and we had the audiotapes. There was an enormous amount of material. So we could easily have made a twenty-five-hour film. Although I think we really tried to find the sweet spot of the story that would be watchable and that would be retain the viewer’s interest over the time that it would take to tell the story.

AX: When you conduct the interviews, is it basically just you, a camera operator and a sound person?

NOVICK: Well, the process on a film like this, for the most part, we spend a fair amount of time with people before we turn the camera on. We don’t just show up with a camera and say, “Tell us about the day your son died in Vietnam.” The camera recording is the end of the process. It goes on for quite awhile. So [co-producer] Sarah Botstein and I were primarily doing this for several years, traveling around the country, meeting people, trying to figure out who we should interview, and then the process of conducting the interviews – usually, if it’s Ken, then Sarah and I, or at least one of us, will also be there with our camera crew, which is also two people, and maybe one other colleague from our production office. And if it was me, then Sarah would be there, and if she was conducting the interview, then I would be there – for the most part, not a hundred percent of the time. It’s always good to have another set of ears, because when you’re doing the interviews, you really can’t hear it the same way that you do when you’re watching it.

AX: THE VIETNAM WAR has an incredible soundtrack. Was there a great deal of discussion of which songs you should use and where they should go?

NOVICK: Absolutely. That’s a huge part of our editing process, choosing music. Every song was carefully chosen, sometimes by our editors, sometimes by Ken or me, or Sarah. We started at the beginning asking our interviewees what music they remember listening to. So that sort of started off our playlist. “What songs do you remember from the time?” Our editors did some of the selecting of what would work in a particular scene, but we would also often didn’t like the choice and would rethink it. So there’s a lot of back and forth about the choices of music. It was really mostly a very collaborative process with Ken and me and Sarah in a room brainstorming, thinking out loud. It was fun to choose.

In the Tet Offensive, we had a moment where we find out that the Viet Cong were going to take over the radio station in Saigon, and they wanted the radio station to play a tape of Ho Chi Minh inspiring people to rise up for the revolution. But the South Vietnamese blocked the transmission and played Beatles songs instead. So we had to choose which Beatles song to put there. Any time you get to choose a Beatles song – which one do you want? – is kind of an overwhelming experience. So we ended up with “Tomorrow Never Knows” in that moment. And then there was a scene later in the film where General Merrill McPeak talks about the music of the time that gave voice to these different forces of protest – the anti-war movement, the civil rights movement, the women’s movement and the environmental movement – and that the music of the time was some of the greatest music that we’d ever produced, and that he turned the volume up. It’s a beautiful moment. So we had to choose what song to put there, and we ended up with another Beatles song, and we all just felt like that really worked, “While My Guitar Gently Weeps.” We went through several songs before we ended up realizing that’s the one that works the best there.

AX: Was there any material, either specifically or a type of material, that you wanted to include but couldn’t get hold of?

NOVICK: On every project, there’s always material that eludes your grasp. Here, I think the more interesting thing for us is the material that our producers were able to find that was very unusual. For example, Mike Welt, our co-producer, tracked down some footage of Kent State that really had never seen the light of day. A man who was a student then had a camera, he was an aspiring filmmaker, and he filmed the protest and the shooting and the aftermath. He was pretty disturbed by all of that, so he put the film in a box and put it in the garage. It took Mike a year to track down the family and the former student and they sent him a box of the film that really hadn’t been looked at in forty years. So that enabled us to take another look at Kent State in a really incredible way. And there are many stories like that. We were able to get really remarkable access to archives in Vietnam and our Vietnamese co-producer Ho Dang Hoa. He just was relentless, persisting in going back to the archives there and asking for more pictures and more footage and different images. I think we represent the work of their perspective very differently than it’s ever been done because of his extraordinary persistence.

AX: It seems like there was a lot more Vietnamese combat footage than one would have expected …

NOVICK: Well, yeah. They understood the power of images to tell stories as well as we do. They had camera crews, they had reporters. They all worked for the government, so in a way, it’s somewhat more analogous to how [the U.S. government] handled the press during World War II. There was very strict censorship and control. But they did want their public to see some of the combat. They didn’t want the public to see images of their soldiers having to kill their severely wounded. Those images we cannot find in their archives, but we have them in our archives.

AX: What are you working on now?

NOVICK: Ken and I are working on a biography of Ernest Hemingway, and that’s a nice break from the epic tragedy of THE VIETNAM WAR. It’s a much more straightforward story to tell, a portrait of one person, but he’s a very complicated person, so I’m sure it’s going to use up all of my remaining brain cells to try to figure that out [laughs].

I’m also directing a film for the first time on my own; Ken is executive producer. I’m very excited about that. It’s a film very different from everything else we’ve done together, it’s a film about people who are incarcerated right now, who are going to college behind bars. It’s an extraordinary story of resilience where you least expect it, and also intellectual firepower. The students who I’ve been following who are incarcerated are extraordinarily talented and work very, very hard, and when they get out of prison, they do very, very well. And they go through a really warp-speed process of education. One of them calls it “the maturing of the soul,” because they just learn to live and to think, to criticize, to understand the world and themselves on a deep level. And we’ve been watching it for three years, filming. So it’s a longitudinal study over a period of time, and people actually are transformed in this process. So that’s coming out next year [on PBS].

AX: And what would you most like people to know about THE VIETNAM WAR?

NOVICK: Ken and I hope that people will be able to watch the film with an open mind and an open heart, because that’s how we made it, and not be quick to judge, and let the stories unfold. We set out ten years ago to find out what happened, we think we have created a coherent narrative of this complicated story, and that people can hopefully stick with it and watch it, and then engage in what we hope will be a really important conversation.

Related: THE VIETNAM WAR Exclusive Interview with filmmaker Ken Burns – Part 2

Related: THE VIETNAM WAR Exclusive Interview with filmmaker Ken Burns – Part 1

Follow us on Twitter at ASSIGNMENT X

Like us on Facebook at ASSIGNMENT X

Article Source: Assignment X

Article: THE VIETNAM WAR Exclusive Interview with co-director and producer Lynn Novick

Related Posts: