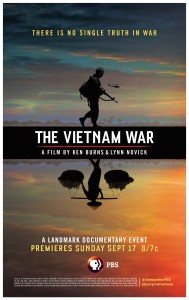

In Part 2 of our exclusive interview, documentary filmmaker Ken Burns reveals more about his ten-part, eighteen-hour series THE VIETNAM WAR, co-directed and co-produced with Lynn Novick. THE VIETNAM WAR airs over two weeks on PBS, Sundays through Thursdays Sept. 17-28.

ASSIGNMENT X: Was there some footage you were surprised existed at all, like the North Vietnamese combat footage? There are times when it seems odd that someone kept a camera rolling.

KEN BURNS: Some of it is for the propaganda purposes, and some of it might be restaged, and we put a disclaimer in the credits on all of them. Including the American stuff. If you’ve got guys training and stuff like that, you know that the Army or the Marines have let them in, and they’ve done that, so in some ways, they’re staged. But I love my job so much, because it educates every part. And when you see this stuff, it isn’t just the usual stuff you get. You dig down, and that’s what ten years [of working on a project] permits you to do. You’re asking for the outtakes of a particular newsreel, or you’re asking for a print of the original camera negative, all of a sudden, you’re getting stuff that, at the time, may not have seemed useful to whatever was being made, but now, years later, it’s incredibly important, and we’re just so grateful that, particularly in this case, the three networks [that were broadcasting during the period – CBS, NBC and ABC], but also the National Archives, were able to provide us with so much material. And the fact that they were able to keep their archives intact and gave us such extraordinary access has been really, really great.

AX: Geoffrey Ward is credited as the writer on THE VIETNAM WAR. Does that mean that he wrote the narration?

BURNS: He wrote the narration. That doesn’t mean to say that that narration didn’t undergo fifteen or twenty different iterations and drafts in which I’m offering changes, and sometimes he and I are writing changes based on what the consultants might have said, or finding out new information. These are scripts that are never written in stone, and we don’t have just a set writing period. We’re always writing, and always changing, but Geoff deserves the credit for having written the narration. Now, we’re constantly providing him with treatments and structures and the transcript of the interviews and what we think is working in those interviews, and the found footage, and things like that. It’s all collaborative, but he deserves every bit of credit for the words there that Peter Coyote reads.

AX: How did you decide on Peter Coyote on your narrator? Was he a natural choice because he had been very involved in political activism for many years?

BURNS: It didn’t have anything to do with his history in the war. I’ve used Peter Coyote since the mid-‘90s. He is a dear friend, I love him like a brother, and he’s one of the best narrators I’ve ever worked with.

AX: When U.S. General Merrill McPeak says at one point in THE VIETNAM WAR, “We are the better for it,” what is the “it” to which he is referring? Does he mean the war itself, the dissent to the war …?

BURNS: I think he’s saying, a lot of people had a kind of love it or leave it, America right or wrong attitude, and he was just saying, look, dissent was part of the thing that I’m defending. And he also understood the huge cultural upheavals that were taking [place] in the ‘60s have produced a whole bunch of movements – not just the antiwar movement, the civil rights movement, the women’s movement, the environmental movement, it also produced, as he said, some of the greatest rock ‘n’ roll, which of course, we have this unbelievable soundtrack to this film. It was stuff that we could not normally have gotten, and had we not reached out to all the artists, or their estates, or the record labels and publishers and said, “Look, we need your help,” we couldn’t afford twelve, let alone the hundred and twenty we want to use, in addition to the original soundtrack by Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross, and the additional music from Yo-Yo Ma and the Silk Road Ensemble. We couldn’t have done any of this, we couldn’t afford this, unless you give us the most favored nations [meaning that all songs received the same licensing fee].

McPeak is just saying, I turned up the volume on that, meaning, it’s good for us to have discussions. When Vietnam comes down to it, this is a negative, this is a failure, this is something we lost, this didn’t turn out the way we wanted, we failed in our objective. But you could also turn that around, and I don’t think it’s being Pollyanna-ish to see the system worked. The courts held up. People began to elect representatives that began to cut off funding for this. The people, as a democracy, the right of people to assembly, happened, and things changed. And the culture went along with it. So I think that McPeak, who is a professional warrior, and it still rankles him that he lost, that he couldn’t do what he did, what he was supposed to do, nonetheless celebrates all of the great cultural gifts that the Vietnam War and that period, in a precise sense, delivered us.

AX: At one point, it’s said that an antiwar demonstration in 1969 is the biggest protest ever. Is that still true, or has that record been broken?

BURNS: I don’t know in terms of the aggregate. Frank McGee is commenting on one of the news [broadcasts], I think NBC, that it was the largest mass demonstration across history, and I don’t know which figure he thinks it is. And since we go in this with the conviction that we are not going to talk about the present moment [in history], that we are not pointing any arrows to this moment, that we’ll just have to leave it to your resources to be able to research whether that happened. We have no political agenda, we don’t have any thumb on the scale, we’re umpires calling balls and strikes here, and we don’t want to say how very much like this is today, even though it’s very clear to anybody with a brain that it is. We can’t focus in our work on that.

AX: How many years is it going to take you to want to make a documentary about the current political situation in the U.S.?

BURNS: I would say I’d need at least twenty, twenty-five years to begin to try to understand it. You’re going to need the passage of time. You don’t even know how this turns out, so it’s impossible to say what’s going on. But I do believe, more importantly, that the past can be an extraordinary guide to this. Once again, without being Pollyanna-ish, you can find in VIETNAM so many antecedents to the current story that it may be possible to see how courts or investigative units or even Congress, the press and people are part of the extraordinarily beautiful, intricate system of checks and balances. And we may look back on this as our finest hour.

AX: What would you most like people to know about THE VIETNAM WAR?

BURNS: It’s not that [there is one single thing to be known]. I would like them to honor the ten years of work that I and my colleagues have committed to this by giving up eighteen hours in however way they want to look at it, and make their own decisions about what they think happened. We’re not in the business of telling people what to think, we’re just in the business of trying to put together a compelling narrative, and we think we’ve done that.

Related: THE VIETNAM WAR Exclusive Interview with filmmaker Ken Burns – Part 1

Follow us on Twitter at ASSIGNMENT X

Like us on Facebook at ASSIGNMENT X

Article Source: Assignment X

Article: THE VIETNAM WAR Exclusive Interview with filmmaker Ken Burns – Part 2

Related Posts: