George Takei is proof that you can take the actor out of STAR TREK, but sometimes STAR TREK is still within the actor. Takei has been world-famous for over fifty years for his portrayal of Starfleet’s Lieutenant Hikaru Sulu on the original STAR TREK series. Sulu was eventually given command of his own vessel, The Excelsior, in the STAR TREK film franchise.

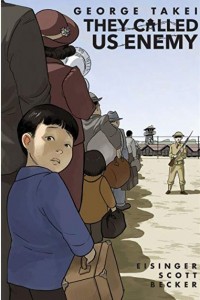

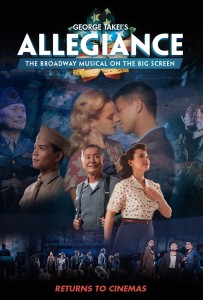

Takei has long since added to his considerable legacy by becoming an author and an activist, working ceaselessly to educate people about the internment of Japanese-Americans by the U.S. government during World War II, as well as for LGBTQ rights. Takei co-wrote and starred in the Broadway musical ALLEGIANCE, about the internment camps. His just-published memoir THEY CALLED US ENEMY, co-written with Justin Eisinger and Steven Scott and illustrated graphic novel-style by Harmony Becker, concerns Takei’s real-life childhood, ages five through eight, in those camps. The book immediately made the New York Times best-seller list.

THE TERROR: INFAMY is the second season of AMC’s supernatural horror mixed with historical fact anthology series THE TERROR, premiering Monday, August 12. THE TERROR: INFAMY is set in and around the internment camps, where the real oppression of Japanese-American citizens is compounded by a vengeful spiritual force.

Takei, with his experiential knowledge of the camps, was hired as a consultant on THE TERROR: INFAMY. He also costars an elderly immigrant to America who is caught up in the raids and sent to an internment camp on Terminal Island, off the California coast.

After doing a Q&A panel with producers and other actors involved with THE TERROR: INFAMY, Takei sits down with two reporters for a more in-depth discussion of the series, as well as his book and the real-life horrors of the camps and the racism that both created and followed them.

This is obviously as serious as subject matter gets, but here’s where Takei’s decades of talking about all things STAR TREK reflexively comes into play. Asked about his character on THE TERROR: INFAMY, Takei begins, “My character’s name is Motohiro Yamato, and others call me Yamato-san. San is an honorific. He was the captain of his own starship.”

It takes a moment for this last bit to register, and then Takei and the reporters burst out laughing. When everyone has sufficiently recovered, Takei continues his reply.

GEORGE TAKEI: I did become a starship captain, but in this project [THE TERROR: INFAMY], he was the captain of his own fishing ship. When he came to America, he was a robust, athletic young man. And now he’s retired, and he spends his life as a raconteur, given that majestic seat on the ship that Henry Nakayama has taken over, and regaling everyone with the tales of my youthful exploits. I’d caught a great big huge tuna, and got it onboard the ship. It was flipping and flopping and rising up, and so I grabbed it and punched it, and thrust it down, and I got the reputation for being the Tuna Boxing Champion of San Pedro. And I’m proud of that. So I’m something of a respected elder. But when Pearl Harbor happens, we’re all rounded up and sent into temporary [makeshift camps].

ASSIGNMENT X: What was your work like as a consultant on the series?

TAKEI: I grew up in two internment camps. I’m consulting on the authenticity of the set, the characters, the historic issues, what followed, and just because the war ended, our being released wasn’t the end of the story. The real horror for me as a child began with our being released. Housing was impossible. Our first home was on Skid Row. The chaos and smell and ugly, scary, smelly people staggering around, and they’re fighting constantly, the men braying at each other, wrestling, or women pulling hair and shrieking, and sirens going day and night. At night, our Skid Row room would glow red from the police lights. I started school and the teacher kept calling me “the Jap boy,” and never called on me when I raised my hand, so I quit raising my hand. The hate was intense, and that was the home our parents said we were coming home to.

AX: How do you feel about mixing a supernatural horror story with the real-world horror of the internment camps?

TAKEI: [Some people think] that the horror story, the ghost tale, is imposed on this story. It is not. It’s organic, because the tension isn’t just between the Japanese-American community and the U.S. government, it’s between the generations within the Japanese-American community, the parent generation, who are more or less the immigrant generation, and their children, who are American-born, and with American values and beliefs. But the immigrant generation brought with them the culture, the beliefs, the rituals, and the superstitions of the old country, and that’s the conflict with the younger, American-born generation, that revolves around superstition. And so with all of this stress of unjust imprisonment, and of being goaded by outrageous demands of the government, superstition has become reality. And when horrible things happen, they attribute it to other forces. And so the horror story is organic to the story of generational conflict.

AX: Without getting too spoilery –

TAKEI: I won’t. [laughs]

AX: Does the ghost have a legitimate grievance with the people it’s menacing?

TAKEI: It’s the spirit of the dead. And also the Buddhist belief of cause and effect, karma, that certain evil that was done in this life will come back in another form, a new generation. They deeply believe that. Buddhists believe in the oneness of life, that life is a continuum, and it doesn’t end with death, that the spirit continues.

Japanese subscribe to two religions [Buddhism and Shinto]. Buddhism is an all-embracing religion. We respect other religions, other beliefs. We believe that life is hard, life is suffering, and if other people can make it through on this journey with their beliefs, more power to them. So we respect Christianity, Hinduism, all the faiths, because that’s their way of dealing with this journey called life. And so we embrace the diversity of human existence, and that incorporates the various faiths. Buddhists don’t go on missions to convert people. We respect people’s faiths.

AX: There are various kinds of Buddhism. Is it specified in THE TERROR: INFAMY which one the characters follow?

TAKEI: No. We don’t go into those specifics, particularly because the immigrant generation, because they’re emigrating to another country [where] the majority are of a different faith, they subscribe to a generic Buddhism. Shintoism is a totally different belief, and Japanese live with both of them. Weddings are conducted in a Shinto ceremony, but funerals are conducted with a Buddhist ceremony, because of the belief in the continuum. In Sunday school, I was given this metaphor. There’s this vast ocean with all these forces that whip the currents, the tides, and so forth, and that produces, at one moment, this wave. And [as human individuals] we’re that wave, saying, “I am me. I have intelligence. I have a soul. I have an ego.” But then the forces of nature bring us back into the larger ocean, and we become part of the natural force, and that’s what human life is.

AX: Even though people have been talking about you for more than fifty years now, some folks still sometimes mispronounce your last name …

TAKEI: It’s often [wrongly] pronounced “Ta-KI” [with a long I] – the “ei” being in the Germanic, Eisenhower, Einstein pronunciation. But if you speak any of the Mediterranean languages, Spanish, Italian, or Greek, the vowels are pronounced that way, “Ta-KAY” [long A]. Like “okay.” Takei.

AX: What can you tell us about your book, THEY CALLED US ENEMY?

TAKEI: Japanese language teacher, judo instructors, the president of the Bonsai Association, [being sarcastic] really ominous, threatening people. They were the first to be rounded up and put into what they called Justice Department detention camps. And on February 19, [1942], President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, and that began the internment process, and camps were being built. But they started rounding us up, and the camps weren’t ready, so in the case of the people in the Los Angeles area, we were taken to Santa Anita race track, and they built a chain-link fence around this once-glamorous racing track, with concertina wires on the chain-link fence, and we were offloaded from the trucks, and herded over to the stable area, and each family was assigned a horse stall, still pungent with the stink of horse manure. For my parents, to take their children and crowd into this horse stall for animals, and make that our home, [it was appalling]. But for me, as a five-year-old kid, I thought it was fun to sleep where the horses sleep. If you breathed deeply, you could smell them. So in my new graphic memoir that was published [July 16], I describe that child’s story. I introduce that story via that child’s eyes, but then the larger harrowing story that my parents were living is introduced. So it’s two parallel stories of that that event.

AX: As both a participant and as someone who lived through the real-world horror, what are your hopes of what viewers get from watching THE TERROR: INFAMY?

TAKEI: Well, my mission in life is to raise the awareness of this chapter of American history. And to this day, I’m always shocked when I share [information about] my childhood imprisonment with people that I consider to be well-informed people, and they’re shocked. I’m shocked that they’re shocked, that they don’t know anything about it. Because so many people don’t know about the internment of Japanese-Americans. And what this show gives me the opportunity to do is to share this chapter of American history. When they use the term “Japanese internment camps,” that really drives me up the wall. Because anyone who knows proper English grammar would know that “Japanese internment camps” would be run by the Japanese government. We are American citizens of Japanese ancestry, ordered by the President of the United States to be imprisoned in the United States in ten isolated prison camps, concentration camps, guarded over by the U.S. military. These were American concentration camps for Americans of Japanese ancestry.” “Japanese internment camps” drives me crazy.

AX: Once you were at the point in your career where you realized you had some recognition and autonomy, is this where you thought you would be at this point in your life?

TAKEI: Well, when I chose to pursue an acting career, my father told me, “I think you should be a lawyer, or a professor, where there’s some dignity to that work.” I said, “Daddy, I love acting. That’s my passion. I love the theatre.” He said, “Look at what you see on TV or the movies. There are stereotyped roles, very unattractive stereotypes, the comic buffoon, or the silent servant, or the villain, usually absolutely evil people. Is that what you want to do?” I said, “Daddy, I’m going to change it.” [laughs] The arrogance of an idealistic youth. And so my goal was to keep my promise to my father, that I would try to build a career where I can play roles of strength, and maybe it may not be the lead, but they’re dimensional, human characters. And now, late in my life, in my eighties, I’m getting those opportunities, and to contribute to raising the awareness of this chapter of American history.

This interview was conducted during AMC Networks’ portion of the Summer 2019 Television Critics Association (TCA) press tour.

Follow us on Twitter at ASSIGNMENT X

Like us on Facebook at ASSIGNMENT X

Article Source: Assignment X

Article: Interview with THE TERROR: INFAMY star George Takei on the AMC series, THEY CALLED US ENEMY and more

Related Posts: