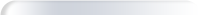

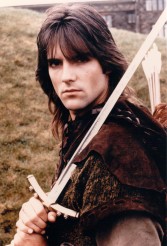

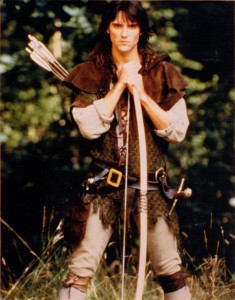

In Part 2 of our exclusive ROBIN OF SHERWOOD interview with actors Michael Praed and Jason Connery (originally published some years ago in EON MAGAZINE), they talk more about their time playing Robin Hood on the British series. Praed was the peasant Robin of Loxley; Connery played Loxley’s successor, the nobleman Robert of Huntingdon. The series is currently streaming on Amazon Prime and Tubi, and available on DVD and Blu-ray.

ROBIN OF SHERWOOD provided an education in much more than on-camera combat for both men. “Just doing a lot of film over the eight-month period, I think I learned a lot,” Connery relates. “I think the thing that’s really difficult as an actor is to believe that it’ll be there if you think it, rather than having to project it. When you work in the theatre, the focus of the audience is directed by the actors. In film, the focus of the audience is directed by the camera. In theatre, if I’m saying to you, ‘I think you’re doing a really good job,’ you need the audience to see you go, ‘Oh, what a liar,’ or whatever it is that you’re doing. Somehow, you have to pull focus, to get them to look at you. I’d done quite a lot of theatre [prior to ROBIN], and I think the mistake is the belief that you have to show. But you don’t on film.” ROBIN OF SHERWOOD proved to Connery that, “On film, you just have to think it, because the camera is right in your face, so if you’re talking to me and I’m saying to you, ‘I think you’re doing a really good job,’ you just have to think, ‘Oh, really? Yeah, I don’t believe a single word you’re saying.’ It’s there in your face instead of needing to express it somehow.”

Praed credits Ian Sharp, who directed ROBIN OF SHERWOOD’s entire first season, for not only teaching him about acting on film but also being largely responsible for establishing a camaraderie that lasted throughout the series, on-screen and off. “He really set the tone, I think. When you thrust a bunch of people together, as you do every time you start a job, you are forced to forge friendships, or certainly relationships, very quickly. But one of the refreshing aspects of ROBIN was there was a complete absence of ego. You can get competitive, which sometimes can leave a sort of ugly taste around, when something other than the work becomes important. On ROBIN, there was none of that. And I think that was almost entirely due to the brilliant psychology employed by Ian Sharp, who completely demystified the camera for all us actors, who were for the most part completely inexperienced.

“I’d been to drama school,” Praed elaborates, “where you’d think that they’d teach you [about performing on film] there, and they didn’t. You didn’t learn anything about lenses or marks. Ian took the time to explain all the lenses, all the different [shot] sizes. And that never happens – people haven’t got the time to teach actors stuff. But Ian was brilliant.

“I have never talked to him about this,” Praed continues, “but because we were all novices, I suppose the great concern is, if you really don’t know anything about cameras, it can be quite intimidating. So Ian would set up jokes in order to [show that the camera] is your friend, it’s not your enemy. Ian was saying, ‘It’s just film. We’ve got more film in the camera. If you f*** this up, we’ll go again. Don’t look at flubbing your lines or walking into a tree as a mistake. It doesn’t matter, and don’t stop, just keep going, ‘cause it might work.’ And oftentimes, those happy mistakes are great. If you wanted to try something different, he said to us, ‘‘It’s still going to be ‘directed by Ian Sharp,’ even if it’s full of your ideas, so if I think your idea is better than mine, I’m gonna use it.’

“Some directors are dictatorial, and that creates a tension,” Praed observes. “Ian wasn’t like that at all. He was bloody strong when he wanted to be, but we had such a relaxed atmosphere on the set. To me, the definition of a fantastic director is a person who can articulate the resolution to a problem in a way that I can understand it, but he has the ability to modify that answer to suit you or him. Ian would do that with great compassion and he was eternally supportive.”

The opportunity to develop his character over ROBIN OF SHERWOOD’s narrative arc appealed to Connery. “That was interesting, because I’d never had that kind of experience with playing a character. Over that period of eight months, we did thirteen hours. In acting, especially on film, you’ve got to use a lot of what is happening to you at that time. I don’t like coming to a scene with a completely set agenda. That doesn’t mean I don’t [prepare], but it means I can use whatever comes up while we’re doing it and allows some unconscious stuff to come up as well. I had some specifics about how I wanted the relationship to be with Marion [played by Judi Trott], because it was difficult. She’d lost Robin and then this other guy [Connery’s character, Robert of Huntingdon] comes along. It couldn’t be just like, ‘Oh, yeah, that’s great, now we’ll be together,’ so there was this whole sort of to-ing and fro-ing. I found that the playing of it was really more revealing than actually having set feelings about it before. I felt like [Robert] started off as a boy and kind of progressed to a man. That’s pretty simplistic in some ways, but in the first episode, my father’s getting on my case all the time – ‘What are you doing?!’ – and [Robert is] very headstrong, but it’s in a slightly teenagey way. I think by the end, he’s realized what he wants.”

The onscreen fellowship between the merry men in ROBIN OF SHERWOOD was echoed in real life. “When people talk about the buddy picture,” Praed provides an example, “take THE STING. Aside from the fact that, in my opinion, it’s one of the greatest screenplays ever written, one thing that’s undeniable, and palpable even, is the genuine affection that Paul Newman and Robert Redford clearly had for each other. It’s visceral, you actually feel this great friendship. When it works really well, it can only have dividends. We genuinely liked each other, and I think that shows.”

During ROBIN OF SHERWOOD’s second season, Praed was offered the role of D’Artagnan in the New York production of THE THREE MUSKETEERS. Praed wrestled with the decision but, although he was having the time of his life on the TV series, ultimately concluded that, as an English actor, he could not pass up the opportunity to star in a Broadway musical. While Praed found MUSKETEERS to be an enjoyable experience in of itself and he’s remained friends with co-star Brent Spiner, the show got bad reviews and closed quickly. “I’ve never been a man to qualify what I’ve done in terms of success; the fact that something has been unsuccessful is not invalidation of the work. I left ROBIN to do this thing, knowing full well what the potential outcome could be, i.e., complete failure. Nevertheless, when it does fail, you can’t but help feel slightly responsible. Other people, in fact, start questioning your judgment: ‘Did you do the right thing here?’”

Praed went on to a year on his first American series, the night-time soap DYNASTY, but found it somewhat rough going as the uptight prince. “I was well-cast in [PIRATES OF PENZANCE] and I think completely miscast in DYNASTY. As an actor, I just felt I was playing the same scenes over and over and, ‘There’s nothing about this character that’s terribly interesting.’ I thought, ‘I don’t know what I’m doing.’ Of course, it took a while for me to admit that to myself, and I suppose at that point, I kind of needed a refresher course.” He starred in several independent films during the next few years, as well as continuing to work in television and stage.

Meanwhile, Praed’s exit from ROBIN OF SHERWOOD heralded Connery’s entrance. Connery says he had some initial trepidation about joining the obviously close-knit cast in ROBIN’s third season. “It was a bit of a baptism by fire. [The other actors playing the outlaws] were all pretty boisterous and they’d all been together for [two years] and they all knew each other really well and I was sort of the new boy.”

The off-screen dynamics actually aided Connery’s performance, as his character, Robert of Huntingdon, begins in much the same situation with the outlaw band. He has happy memories of a sequence in which Robert and Ray Winstone’s Will Scarlet bond by brawling. Scarlet breaks a jug over Robert’s head in a shot that required multiple takes, when the pottery refused to shatter on cue. “The thing with Ray, that was great fun. We’d done two episodes before the first [in story order], but that was the one where [the other characters] all met me. Not that they had done anything to suggest that I wasn’t before, but that was where I really began to feel like I was part of the gang.”

It was sometimes a battle for Connery to look as though he was a member of the gang, he remembers. “Physically, [third season] looked very much like the series before, although they didn’t have the same continuity, because they had lots of different directors. They always wanted me to look really clean. It took me weeks of arguing to get any dirt on my face and they gave me that sort of Linda Evans hairstyle. It used to drive me mad, because everyone else looks like they’ve been shoveling s*** uphill, so I’d get out and …” He mimes smearing dirt on his face.

The ROBIN OF SHERWOOD regulars continued to socialize heartily together off-camera. “I look back at it with rose-colored glasses,” Connery muses. “We were known as the Merries, and we hung out, and we had a good time. A lot of the guest stars were really good fun. Ian Ogilvy [who played Robert’s Uncle Edgar] was very mature when he came on – he had a pipe and everything. We kept thinking, ‘This guy looks like he needs to have a bit of fun.’ So we said to him, ‘Look, it’s tea time – come down, they have great cakes.’ We were out in the middle of a field at a big table. The caterers called themselves [by the acronym] First Unit Caterers Kitchen. They had these amazing cakes. I said to Ian, ‘Does this cake smell off to you?’ It’s got great big cream coming out of it. He takes it, and of course, I go,” Connery gestures pushing Ogilvy’s éclair-laden hand into the actor’s face. “And then it’s off. Everybody’s throwing the cakes. There was a mud fight as well, when it rained the next day. He had the best time – he still talks about it.”

Flubbed takes were a source of general amusement. “I remember one scene as being just a disaster,” Connery laughs. “There were a lot of extras around me, and I had to describe some plan of how we were going to go into the castle. It was some really easy line, and I just couldn’t get it right. All the extras are like, ‘What’s he doing?’”

Some of Connery’s favorite onscreen moments involve the Robert/Marion romance. “The scene [in ‘The Time of the Wolf’] where I come back to Marion and she’s waiting in the church and she thinks I’m dead and then she sees me – I enjoyed that because there was an emotional scene. Also, there’s a scene [in ‘Rutterkin’] – it was the middle of the summer and it was hot and there were piggy-back fights. Friar Tuck [played by Phil Rose] was carrying me. I see that episode, and most of the time, I’m rolling around the ground laughing.”

Asked if there are any scenes he’s especially proud of, Praed considers, then replies, “It’s a tiny little thing [in ‘The Witch of Elsdon’], when I had to listen to [a character who] was telling me what turned out to be bulls***. Ian sat me down and said, ‘You know, actors often forget to listen when people are talking.’ Somebody’s on a cart, and they’re just talking to me, and I’m just standing there listening, and I put into practice what Ian had said. I’m not actually doing anything. Maybe I like that because I realized how much I didn’t know about the technique of filming, and this one tiny little door opened, and I thought, ‘Right. Must remember.’”

There are conflicting theories as to why ROBIN OF SHERWOOD did not proceed beyond its third season. The collapse of primary funding entity Goldcrest Films seems to have been a major cause. Preparations had been made to continue. Trott would only be intermittently available, so her character Marion’s occasional absence in the planned fourth season had to be explained. Third season therefore ends as Marion enters a convent rather than risking marriage and widowhood a second time. Had the series gone forward for another year, Connery says he would have liked, “First of all, sorting out the Marion thing.”

Praed says that had he stayed with the show, “It would have been intriguing to have an episode on the nature of violence, for example. How does that actually affect somebody [living as an outlaw]? I’m saying that now, but I’m older now. In those days, I never really thought about it. I thought, ‘This is not my domain. This is somebody else’s right, and somebody else’s job.’ Now I’m more interested in that.”

As their careers have gone forward, both Connery and Praed remain touched by the continued interest in ROBIN OF SHERWOOD. Connery would prefer not to try to pinpoint why the show has had such a lasting impact. “I hope it is a mystery, because I think anybody who thinks that they can bottle that knowledge are going to fall on their asses pretty quick. I’m so happy when concept movies where you get, ‘Oh, well, we know that works and we know that works,’ and they spend lots of money, and [the movies] just disappear. And then someone will come out with an original idea [that’s a hit] and everyone will say, ‘But that’s never worked before!’ So I hope nobody can say why.”

However, Connery allows that sometimes imitation can be the sincerest form of flattery. “A compliment that I really took very highly was, I [met] Ron Howard. He said to me, ‘You know, I took a lot of stuff from you.’ I said, ‘From me?’ He said, ‘Well, no, not from you, but from [ROBIN OF SHERWOOD], when we did WILLOW.’ And a lot of that look in WILLOW, when I think about it, all the villagers and the bad teeth and the broken-down village was what I liked about ROBIN – it looked pretty earthy. It ages well. [If a show is] meant to be contemporary, five years down the line, it just looks old-fashioned. Whereas ROBIN is set in period, and therefore, it has a lifespan.”

“It’s quite difficult to date our Robin Hood,” Praed concurs. “The fact that it was medieval helps, and the music by Clannad is such an inspired choice, because that really is timeless. I was really pleased with the look of it, the shadows and the smoke and the texture. I just thought the way it was shot – unlike lots of things, they really used light as an art form, and not just to expose the negative. And things that aren’t immediately obvious. For example, [Sharp] got a feature film sound guy to do all the sound effects. And that sounds like, ‘Yeah, so what?’ The answer is, it sounds bloody good. I remember thinking, ‘This actually looks new, sounds different.’”

As for ROBIN OF SHERWOOD’s continued following, Praed says, “I’m absolutely delighted. Obviously, it’s not without precedent, but in my life, in my career, it is. I’m really proud to have been a part of that production. And it does give me a good feeling. People still want to watch it – we did something right.”

Follow us on Twitter at ASSIGNMENT X

Like us on Facebook at ASSIGNMENT X

Article Source: Assignment X

Article: Exclusive Interview with Jason Connery and Michael Praed on starring in the 1980s U.K. series ROBIN OF SHERWOOD – Part 2

Related Posts: