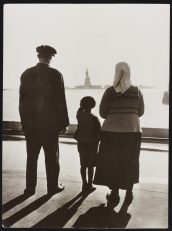

THE U.S. AND THE HOLOCAUST is a meticulously-researched documentary miniseries about what Americans did – or often did not do – to address the rise of fascism and genocide in Germany, and around the world, before, during and after World War II. The parallels to contemporary events are terrifying.

The six-hour film airs on PBS over three nights – Sunday, September 18, Tuesday, September 20, and Wednesday, September 21 – in two-hour installments.

The film was directed and produced by prolific documentarians and frequent collaborators Ken Burns, Sarah Botstein, and Lynn Novick. Novick was a director/producer with Burns on the documentaries FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT, THE WAR (about World War II), BASEBALL, PROHIBITION, THE VIET NAM WAR, COLLEGE BEHIND BARS, and HEMINGWAY. Botstein was a producer on all of these except BASEBALL, where she served as a program advisor. Additionally, both Novick and Botstein were producers on Burns’s documentary series JAZZ and advisors on THE ROOSEVELTS: AN INTIMATE HISTORY.

Botstein and Novick, in separate locations, get on a Zoom call arranged by PBS as part of the Television Critics Association (TCA) summer press tour to discuss THE U.S. AND THE HOLOCAUST.

ASSIGNMENT X: How did THE U.S. AND THE HOLOCAUST originate?

LYNN NOVICK: The inspiration was a meeting that we had in 2015 with the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington. They let us know that they were planning an exhibition on the topic of Americans and the Holocaust, which was going to open in 2018, and they suggested that we might be interested in making a documentary on the same topic, and that we work in tandem with them. Ken, Sarah, [writer] Geoffrey C. Ward and I all immediately had the “aha” moment, “This is a terrific idea for a documentary.”

We had focused on the Second World War; Ken and Geoff made a series about the Roosevelts. The question of America’s response to the Holocaust is something we had dipped into very little, not really focused on as this primary interest in any of the work that we had done. We realized there was a lot that we actually didn’t know, questions we had that we wanted answers to about what we knew, what we [as a nation] did, and what we failed to do. We started thinking about the project, and committed to doing it, in 2015, but we didn’t really start production in earnest because we had a long slate of projects already underway. So, we started production in earnest production in 2018.

AX: Because you had so extensively covered World War II in other projects, and what shows up onscreen is a fraction of what you put together for those documentaries, were you able to use material you’d acquired but didn’t get onscreen for those other documentaries in this one?

SARAH BOTSTEIN: That’s an interesting way to think about how we use archival material. Certainly, we didn’t use any interviews or any cinematography that we filmed for either of THE WAR or THE ROOSEVELTS in this series. I’m sure there’s archival material from the time period – I think the landing at Normandy is in all three of those films. Certain images of Roosevelt, radio broadcasts, iconic moments of Second World War history that particularly involve the White House, Congress, and Roosevelt, Pearl Harbor, those events show up in many of our films. Lynn, Ken, and I all really love to talk about when we tread over the same time period from the lens of a different subject, and how we can look at them differently, based on the subject matter of the film. So, we often will use similar, if not the same, archival material in different films, depending on the subject of the documentary. But no “outtakes” from [the team’s other documentaries] ended up in this film. We shoot all the original content new for every film.

AX: What’s the division of responsibility between the two of you and Ken Burns?

NOVICK: That’s a little bit of a hard question to answer, because what we mean by “directing” is [deciding on] the overall sense of what is in the film, what isn’t in the film, how we’re going to tell the story, what is the story we’re going to tell, who we’re going to interview, what we’re going to ask them. Working with our writer, Geoff Ward, on the script, and then working with our production team with all the archival materials and the music, Ken, Sarah and I are all involved in all of those things.

For each project, it shifts a bit, depending on what we’re all working on. In this case, Sarah and I did the lion’s share of the interviewing, tracking down the witnesses, and figuring out who would be good people to represent this time period. But other than that, we really collaborate, rather than divide up on all the aspects of the filmmaking.

AX: You use some period comic strips to illustrate certain points in the documentary. Are those cartoons that were actually produced during the era, or did you commission those to be drawn in period style?

NOVICK: [laughs] Those are straightforward lifts from newspapers, sometimes with relatively well-known cartoonists of the era. The only thing that we commissioned that’s new graphically are the maps for the series, and sometimes if we have a magazine fold, or some kind of newspaper, we might film that differently. But we would never recreate the actual document.

AX: Both of you are Jewish-American women, as am I. How aware were you before you started working on THE U.S. AND THE HOLOCAUST, or even when you were growing up, of the things discussed in the documentary?

BOTSTEIN: It’s always hard to think back on what you knew before you started making a film. On my father’s side, I’m a first-generation American. My father came here as a refugee in 1949, so I knew a little bit about the Holocaust, and I had impressionistic notions of this history, but I didn’t know anything about any real policies. I’d heard of America First, and Charles Lindbergh, and I had heard about the St. Louis, and I knew that it took my grandparents a really long time to get here, and that my great-grandparents couldn’t get here, so they were in a Holocaust community in Mexico City. I knew little pieces of it, but I didn’t know the whole story, and I think actually many Americans, Jewish or not, also have impressionistic notions of what happened during this time, but less real facts of what was happening, and what U.S. policy was as the crisis was unfolding.

NOVICK: My perspective is a little bit different than Sarah’s, in that this history was pretty remote to me growing up, it’s not something that we talked about a lot. I was born in 1962, so when I think about it now, it wasn’t that long after the Holocaust and World War II. My parents were children and teenagers during that time, growing up in New York, and I think they were somewhat insulated, frankly, from what was happening, didn’t have any direct connections to people overseas, or to refugees, or to people who were killed. And so, it was a humanitarian catastrophe and a tragedy – fairly abstract, something that happened far away, over there. There were a lot of big numbers, there were horrible images of emaciated people, and piles of bodies, and things that I could barely stand to look at, or even really begin to comprehend. I never studied it in school – this didn’t end up in the curriculum until after I was done with my education.

So, my understanding of the Holocaust came from books, documentaries, and Hollywood films, and foreign films, which doesn’t give you the whole picture by any means. And I really didn’t know anything about America’s response. That’s another layer that just was not something that was of great conversation. That said, I certainly had an understanding of anti-Semitism and racism in America, and they were seen in the way I grew up as somehow part of our story that we need to deal with. But I hadn’t asked the central questions that we ask in this film until we started working on it.

AX: What would you say are those central questions? And did you ask the questions in terms of getting it out there to the viewer, or did you ask the questions because you actually wanted to know the answers yourselves?

BOTSTEIN: Both.

NOVICK: That’s what drives us, really, in making these films. If we just make a film to tell you what we already know, as Ken always says, it’s not a very interesting exercise for us as filmmakers and amateur historians. So, for everything I’ve ever worked on, and I think that’s true for Sarah, Ken, and Geoff as well, we really do start out, on a fundamental level, to answer questions to which we don’t know the answers. And then we hope that when we explore those questions, sometimes there are no easy answers, sharing that with our viewers is the ultimate goal. So, it’s really both. We very consciously go in, not to make an argument or to prove a point, but to learn something for ourselves.

The questions for us are really the questions I think that [Holocaust historian] Rebecca Erbelding says at the beginning of the film – what did we know, when did we know it, what could we have done, what should we have done? And if we didn’t do more, or enough, why was that? Ultimately, it’s connecting what happened in Europe, the events that we now call the Holocaust – that name was not applied to those events at the time – and what did the American people understand about these events as they were happening, and what was our response?

AX: You start THE U.S. AND THE HOLOCAUST by giving us new information on the Anne Frank story. Did you start with Anne Frank because everybody feels like they know that, whether or not they actually do, to ease people into the subject matter with something that isn’t completely alien?

BOTSTEIN: We really thought long and hard, as you might imagine, how to start a film like this, and how to communicate to our viewers what this was going to be about. When we found out while we were making the film that Anne Frank’s family had tried to come to the United States multiple times, in different ways, that really was a lightning bolt of, “Oh, we can help our audience understand that the story of the Holocaust is connected to the United States, and to America, and that we’re going to find ways to intertwine these narratives. Who better to do that with than Anne Frank, who most Americans, or most viewers, have heard of and know about?” We assume that most people, like us, probably didn’t know that her family tried to come here. Framing our film around that interesting and devastating information, we hoped, would help our audience and ourselves get a handle on what this whole overarching story was.

AX: You said you didn’t actually get underway until 2018. At that time, had the subject matter acquired an urgency that it didn’t have maybe quite so much before the administration in Washington at that time?

NOVICK: I think when we first got our heads around making the film in 2015, not only was domestic politics and the situation here very different, but the situation around the world was very different. So, yes, while we were really getting underway and starting to do interviews and putting the script together and begin editing, our country was changing, the world was changing, and so some of the questions that the film wrestles with, and attempts to either answer or explore, became more relevant in certain ways. And then, as we were finishing the film, the Russian invasion of Ukraine happened. So, it took on another meaning even when we were creatively done with the film.

In all the films we’ve worked on, what’s happening in the current state always informs some of how we think about the subject, but for this film particularly, the questions that the film is wrestling with are very prevalent, not just here, but around the world. What kind of a country we want to be, what do we do in moments of world crisis? Are we a land of refugees and immigrants, does nativism/anti-Semitism/racism win out?

AX: Were you surprised to learn that Adolf Hitler admired white American genocidal methods used against Native Americans?

BOTSTEIN: Quite surprised. Perhaps we shouldn’t have been. Speaking for myself, I had not done a very deep dive into Hitler’s ideology. I had read MEIN KAMPF and I knew a fair amount about Hitler, but I did not know his early musings about what would make a great country, and his aspirations for Germany to emulate the United States in these two horrific ways of exterminating or containing native populations and segregating and subjugating African-Americans as second-class citizens. Those were the two takeaways that he most admired, and he and his Nazi colleagues really studied what America had done and was doing – they didn’t want to have to reinvent the wheel, as horrible as that is to say. And we have to really take stock of that.

AX: To make a broad generalization, most PBS viewers are not, say, Proud Boys, Oath Keepers, or members of other fascist organizations. But do you have any concerns that somebody with a fascist philosophy is going to look at THE U.S. AND THE HOLOCAUST and get new information about eugenics and glom onto it, and go, “Aha!”, or do you feel like you’re mainly educating the mainstream population so that we don’t repeat history?

BOTSTEIN: We’ve spent a lot of time in the last few months thinking about and beginning to understand how different groups take documentary evidence, or repurpose things. I think we feel strongly that we wanted to tell as honest and clear-eyed a history of this time period as we could, and create educational materials to accompany the film, and to try to get curriculum into schools, and create viewers’ guides for interested Americans to watch the film and talk about themes in it. We can’t get too distracted by what could happen with the material that we’ve created in that way. I think that’s a really scary and sad part of what goes on, and we felt like it was really important to tell the history.

NOVICK: Yeah. I think while we were making the film, we’ve seen, as your question implies, a resurgence and a mainstreaming of some ideas and movements. Words like “alt-right” and “white nationalism” and “far right” don’t begin to really capture the essence of what some of these groups are. Call it like it is. Deal with what these people are saying and what they’re espousing. It’s explicitly white supremacist, hateful bigotry and prejudice against a number of groups. They plug in different groups, depending on who they are, but that’s what we’re seeing. We’re seeing this really barbaric ideology go from the far fringe to the mainstream. That’s what we are concerned about, and we do hope that telling the story, like Sarah was saying, is a reminder of just how dangerous these ideas are, and how quickly we can go from a democracy to totalitarianism.

AX: What would you both most like people to get out of THE U.S. AND THE HOLOCAUST?

BOTSTEIN: My answer to this question, which we’re getting a lot from various reporters, is, this sounds a little bit cheeky, but it’s really important to vote, it’s a privilege to live in a democracy, and you should be an engaged citizen. Your local school board, your local Senate race, your local Congressional district. Voting really matters, and as Lynn was just saying, we talk at the end of the film about how quickly democracies can fall, civilized institutions can crumble, and the privilege of voting can be a push against that. That’s my takeaway.

NOVICK: I agree with that completely. If I were to just circle back a little bit, we’ve tried to tell a story that we recognize is at times painful, and sometimes challenging, about our response and our failures and our shortcomings and a whole complicated human story of a very difficult time in human history.

Sarah and I did a radio call show the other day, and somebody called in and said, “I’m glad you made the film, but I don’t want to watch it, because I can’t take another Holocaust story.” Our feeling is, we really want people to watch this, because it’s an important chapter in American history. With all the problems that we were talking about today, with white supremacy, with the fragility of democracy, you can’t understand anything about what’s going on now if you don’t fully appreciate what happened then. So, it’s really just to frame where we are by understanding this particular series of events has been really helpful to us, so we’re hoping that people will take that away.

AX: It seems less like a Holocaust story than a, “We’re living in very frightening times” story …

NOVICK: Exactly. That’s why I said that, because we want to say to people, “No, no, we’re not doing another Holocaust movie like all the other ones that have been made.” There have been some amazing, incredibly important films that have been made. This is a different kind of story, about what you just said, and what I just said. Why are things happening now the way they are?

Follow us on Twitter at ASSIGNMENT X

Like us on Facebook at ASSIGNMENT X

Article Source: Assignment X

Article: Exclusive Interview with THE U.S. AND THE HOLOCAUST Directors-producers Lynn Novick and Sarah Botstein

Related Posts: