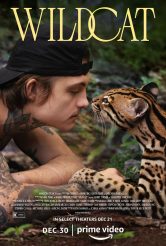

Premiering in theaters on Wednesday, December 21, and available on Prime Video on Friday, December 30, WILDCAT is a documentary about trying to teach a young ocelot to live and hunt in his original surroundings. The film, shot primarily in 2018 and 2019, chronicles the efforts of then-University of Washington biology student Samantha Zwicker, originally of Bainbridge Island, WA, and young British Army veteran Harry Turner to “rewild” one ocelot kitten, Khan, and then a second, Keanu, in the Peruvian Amazon jungle. (Coincidentally, the documentary comes from Amazon Studios.)

Since WILDCAT wrapped, Zwicker has graduated with a PhD and greatly expanded her rescue, research and rewilding activities with Hoja Nueva. Located well off the beaten track in the Peruvian jungle, Hoja Nueva specializes in helping wild South American felines who have somehow come into human hands reacclimate to living in nature.

Zwicker gets on a phone call to discuss both WILDCAT and Hoja Nueva.

ASSIGNMENT X: BORN FREE is an extremely famous rewilding true story of a big cat, but it took place in Africa, and involved lions. Are you and Harry Turner the first people to have done this with ocelots in Peru?

SAMANTHA ZWICKER: Yeah. A lot of people have tried it with bigger cats in different areas, but small cats can sometimes be more complicated. And in this particular case, it was an ocelot, but also, in this type of environment, in the lowland Amazon, a lot of reintroduction hasn’t happened, because it’s not a focus. Five thousand animals a year are seized in Peru, and there’s often nowhere for those animals to go. Before we developed Hoja Nueva, specialized in carnivores, and built a carnivore rewilding center, there was no center focused on that. So, [Keanu in WILDCAT] was the first ocelot to be reintroduced and documented.

AX: How did Hoja Nueva come into being?

ZWICKER: Post-WILDCAT, we [the eventual Hoja Nueva team] were hyper-focused on, “This [a rewilding program] needs to happen, there’s a giant need.” Especially amidst the pandemic, wildlife trade and trafficking increased greatly. So did bushmeat hunting. So, we decided in 2020 we were going to become a registered rescue and conservation center, focus on carnivores, and we built this first-even specialized center to focus on rehabilitating them for the wild. And we’ve maintained that over the last two-and-a-half years. It’s been our primary focus.

But we have three pillars – we do rewilding, we do ecological research, and then applied conservation efforts. So, land protection, working with local communities, doing some sustainable development community efforts. And then on the research side, we actually get to cross over quite a bit, researching and rewilding. Our research over time has been primarily on wild populations, and how wild populations of species like ocelots are being affected by human impact, and different levels of human activity, and how that causes a ripple effect within the ecosystem, and also changes the way that species are interacting with each other. So, we’ve got some really exciting research, and oftentimes, the rewilding plays a huge part in learning more about these species along the way.

AX: During WILDCAT, you were working on your university degree. Is the University of Washington involved with Hoja Nueva, or this is now you on your own with the Hoja Nueva team?

ZWICKER: Yeah, this is kind of me on my own. I think I’ve always done things a little bit differently throughout my Master’s and PhD. Hoja was always kept kind of separate, for multiple reasons, but [the university is] definitely very supportive. We now have our first college Study Abroad group that’s coming from the University of Washington to come to our new research center. So, we make connections that way, and we maintain that relationship, but it’s separate from the rewilding and how Hoja was created and what it’s morphed into now.

AX: Was WILDCAT the documentary originally designed as a fundraising tool for Hoja Nueva?

ZWICKER: No. I think the issues, especially the ones that I like to raise awareness for and create around, in terms of wildlife trade and trafficking, they do take a little bit of a back seat in the film, and so, we haven’t been able to use it as much as a fundraising tool for that. I definitely do my best, with the support of the film team and Amazon, to go to events and talk to people as much as possible about the issues of why we received baby ocelots in the first place and those types of things, so that we can raise that type of awareness and hopefully create change, and get people to support our work.

AX: So, how did WILDCAT the documentary come about? Were the documentarians already there to make something else and it turned into the documentary about rewilding, or did they come in sometime during the process after you and Harry Turner had already documented a lot of what you were doing, or …?

ZWICKER: They came in sometime during the process. Back when we rescued our first ocelot, Khan, I made it my mission to document his life from the very beginning, for research purposes, to learn more about the rewilding process of ocelots in general, and be able to share it with the world, but also, just for ourselves and to document his life. And so, I bought a Sony cam, and we would film pretty much every step of the way his life for those eleven months.

It wasn’t until I think a friend of a friend told Trevor Frost, who I think at the time was doing a shoot in Peru for National Geographic, someone pointed me and Harry [Turner] out in a hotel and said, “You should hear this story about raising this ocelot, and how it ended.” Trevor was extremely interested, and we had archival footage, and then got his partner Melissa [Lesh] on board. At first, it was going to be a short documentary, just about Khan. And when we rescued our second ocelot [Keanu], they had the idea to follow it in real time, and to create more of a feature-length film. But I don’t think anyone imagined it would be where it is right now [laughs]. But at the time, something we were really passionate about was memorializing Khan and sharing the story of both of them.

AX: What other sorts of animals do you deal with at Hoja Nueva?

ZWICKER: We’ve built this carnivore center specifically for cats, so we’ve got in our care right now jaguars, ocelots, and margays [a feline that resembles a small leopard], primarily. But we also specialize in other meso-predators, like coatis and kinkajous and tayras. Those are some of our biggest ones. We’ve also taken in pumas and jaguarundis, which are the two remaining cat species that we have in our region, and then also oncillas, which is like a very, very small version of an ocelot, but they’re only located in some of the upper reaches, a little bit higher elevation of tropical forest.

We get lots of coatis from the pet trade. They’re very common, people like to have them as pets, until a certain age, when they become extremely volatile [laughs]. We just rescued six coatis at one time. That’s probably the most common animal that we get sent from the government.

AX: How does the government get the animals in the first place?

ZWICKER: Oftentimes, the government actually seizes the animals from people. There’s a new system in Peru where you can anonymously report wild animals as pets, so that’s a huge source of information for the government. So, local, regional, and the federal government get these kinds of notices, and then, as soon as they know what the species is and how old it is, they contact us if it’s in our specialization, which is generally for any animal that comes up these days. They contact us first to see if we have room to receive it. But they also do larger operations, like shutting down illegal zoos. We’ve helped at the federal level to shut down a few [illegal] zoos around Peru. And at that point, it’s taking in forty animals at once. It just depends on the situation.

AX: Because Hoja Nueva is a predator center, how do you keep the larger predators from attacking the smaller predators when you’re trying to rewild them?

ZWICKER: At our center, we have enclosures for each individual animal that are integrated into the natural environment, and extremely deep in the jungle, but separated. So, we’ve got an entire section that’s more for ocelots, one for the smaller margays, we’ve got an entire section for big cats, and then we’ve got sections for things like tayras and coatis.

So, they’re raised completely separately, and then we have release plans, where we strategically release animals on different areas of our property, and sometimes even other areas in general. We received a baby jaguar recently from Loreto, which is a different region [in Peru], and we’ll have her for about a year and a half before we reintroduce her back to Loreto with partnerships with the government and local people there.

AX: It seems like Hoja Nueva would have a larger physical footprint than you had during the period of WILDCAT. Back then, literally, how did people physically find you to get the baby ocelots to you?

ZWICKER: Physically, it’s not super-possible, even now [laughs]. You’d have to organize it with us – we’re impossible to find. In the beginning, when we started, we were really focused on community efforts, and agri[culture]-forestry, with research on the side, and then the effort of rewilding, it grew, based on Khan and Keanu, and those types of efforts are the ones that require lots of funding. I was able to work on a shoestring budget for the first couple of years, doing the projects that I was doing back then, and we really had to grow to a point where we can sustain our current efforts.

We’ve got, I think, sixty-seven animals currently in our care, which means around fifty enclosures that had to be built, and a veterinary center that had to be built, and a lot of effort that goes into the process of rehabilitating animals for the wild that have come from all types of backgrounds, where they’ve been physically abused, been in zoos for years, psychologically need so much care that sometimes lasts years, and that type of effort can be costly. So, I’m really grateful that our work is getting out there into the world a little bit more. We need it now more than ever as we grow.

AX: Now that you have a veterinary center, are you more equipped to deal with things like spider bites, and other potentially fatal issues that come up in WILDCAT?

ZWICKER: Yeah. We can deal with pretty much anything, any type of case. The government will bring us animals that sometimes have had an injury and their leg needs to be amputated. So, we can deal with surgical cases on site now. We’re fundraising to get a little bit more equipment that’s very much necessary to amp up our efforts a little bit, but for the most part, it’s been life-changing to have veterinarians living on-site that are part of our programs, where the case is, the more animals you take in, the more you’re going to get cases where something is very much wrong, and you can’t always tell what that is in the beginning. And so, having those facilities and those people is really vital as we accept more animals over time.

AX: With animals that are amputees, it seems like they wouldn’t survive being released back into the wild, so what do you do in those cases?

ZWICKER: If there’s a physical impairment like that, which we’ve come across several times, we generally don’t take on those cases. We help the government facilitate them going to a really good sanctuary. There are not too many that exist, unfortunately, but we’ll facilitate that. But if there’s nowhere else, we’ve never yet had to tell them, “Okay, euthanize this animal,” which is generally what they would do, and what they did before we existed. But we only have four in our sanctuary right now. The rest of our sixty-seven animals are in the rehabilitation for rewilding program. But we have a blind margay, and then we’ve got an ocelot that has three legs – that was the amputee that I told you about. Every once in a while, there’s enough psychological damage from spending time neglected in the back room of a zoo for years at a time that they just can’t overcome, and so we do have two that are like that.

AX: They just want to sit there and get fed and soak up the sunshine?

ZWICKER: Yeah. One kinkajou has panic attacks, like seizures. He does it a lot less now, but it was a reaction to being in this really intense zoo setting, and then, when the pandemic hit, the zoo just left their animals. Most that we found were deceased, but we found a kinkajou in the back corner in a box. He hadn’t eaten for what could have been at least two weeks, and so we think that he came through with some of his issues. He’s suffering less from the seizures, and he’ll be with us forever, and we’ve given him a very good life. He could be with us for very many years [laughs].

AX: If people want to donate to Hoja Nueva, or find out more about the project, they can just go to HojaNueva.org?

ZWICKER: Yes. They definitely can. We’ve got a support page, multiple ways to donate. Anything is very much helpful, especially now.

AX: And what would you most like people to get out of watching WILDCAT?

ZWICKER: Apart from that, I guess just self-educating about these issues, and how people play a part on an individual level – responsible consumerism, responsible tourism. Tourism is huge. Especially after the pandemic, lots of people are traveling again. Just getting people to understand that buying wildlife parts that are being sold in the markets in different places, or taking photos with baby animals, those types of things all contribute to [harm to wild animals], and is something we’re working really hard to stop.

Follow us on Twitter at ASSIGNMENT X

Like us on Facebook at ASSIGNMENT X

Article Source: Assignment X

Article: Exclusive Interview with ecologist Samantha Zwicker on new Amazon Studios documentary WILDCAT

Related Posts: