Chol Soo Lee was a young Korean immigrant living in San Francisco’s Chinatown when he was arrested on June 7, 1973, and subsequently convicted, for the murder of Yip Yee Tak. While in prison, Lee was given the death penalty for the killing of a fellow inmate, although Lee claimed self-defense.

In June of 1977, reporter K.W. Lee (no relation to Chol Soo), after hearing from young Asian-American activists, began investigating the case for a series of articles in the SACRAMENTO UNION. K.W. Lee found facts that strongly suggested that Chol Soo Lee had been wrongly targeted for the murder of Tak due to a combination of racism, bias about his institutionalized background (he had been in both juvenile hall and mental health facilities), and police and legal malfeasance.

The articles appeared in January 1978. These prompted the formation of the Chol Soo Lee Defense Committee, which was founded by Chol Soo’s friend, third-generation Japanese-American Ranko Yamada, third-generation Korean-Americans Gail Whang and Brenda Paik Sunoo, recent law school graduate Jay Yoo, and schoolteacher Grace Kim.

In turn, the Chol Soo Lee Defense Committee brought together Asian-Americans of different ages and backgrounds, as well as others, in what has been called the first movement of its kind in the Asian-American community.

Now, filmmakers Julie Ha and Eugene Yi have made the documentary FREE CHOL SOO LEE, about the case, the activism surrounding it, and the aftermath. The film premieres on PBS’s INDEPENDENT LENS on Monday, April 24. It previously screened at the Sundance Film Festival, and was the runner-up for the Library of Congress Lavine/Ken Burns Prize for Film.

Ha and Yi, together with activists/interview subjects Whang and Yamada, sit down together to talk about FREE CHOL SOO LEE during PBS’s portion of the Winter 2023 Television Critics Association press tour in Pasadena.

ASSIGNMENT X: When did you first become aware of Chol Soo Lee?

JULIE HA: I became aware of the case when I was eighteen years old, and I was doing an internship at the KOREA TIMES English edition, whose editor was K.W. Lee. When I learned about Chol Soo Lee’s case, K.W. ended up becoming a mentor and inspired me to want to do the film.

EUGENE YI: I also knew about it through K.W. Lee. I met him about twenty years ago. It was one of the most important stories of his career.

AX: How did the two of you come together as filmmakers for this?

YI: We first came together as print journalists. Julie was editor-in-chief, before that, editor, of KoreAm JOURNAL, and I was one of the writers. So, we had that working relationship, usually [doing] longer-form, like deep dives into various Asian-American issues.

HA: Yeah. Eugene and I had known about the case for quite some time, but in terms of making a film, the seeds of that weren’t really planted until the funeral of Chol Soo Lee in 2014. I had gone to the funeral, and Ranko and Gail were there, and I was writing an obituary for the magazine Eugene and I worked for, but also to check on K.W. K.W. had become somewhat of a father figure to Chol Soo. He was terribly anguished that Chol Soo had passed so suddenly.

And while I was at the funeral space, I just felt this overwhelming sense of heaviness. I was struck by what some of the other activists were saying about Chol Soo. One of them said that she would always regret not doing enough for him, and at one point, K.W stood up. He was very emotional, and he said, “Why is this story still underground after all these years?” He was lamenting how this landmark Asian-American social justice movement, the first of its kind in this country, and really a landmark American social movement, was not known. It was not even taught in Asian-American Studies classes at American universities and colleges, and he knew how singular this history was, and this movement, and also how consequential.

So, fast-forward to Eugene and I talking about making a film together. We’ve always shared a passion for especially tackling complex Asian-American stories, and trying to tell them with nuance and depth, and we felt like we just had to excavate this story that had been lost, and was at risk of being buried in history.

AX: You were friends with Chol Soo Lee before the case happened?

RANKO YAMADA: Yes. I had known him from Chinatown, prior to his arrest. He hung out there. I had a job there in a tourist pearl store. I just met all of these young people that were hanging out up and down the street in Chinatown. This was their backyard. They didn’t have yards [laughs].

AX: Is that what inspired you into activism?

YAMADA: No, I was [already] pretty involved in different things.

GAIL WHANG: And I met him after I heard about the case, and after reading K.W. Lee’s article, and hearing K.W. speak. Another friend got us together to hear about this incredible case. And just reading the article, and meeting K.W., and hearing his passion, that did it. At that point, I did not know Chol Soo Lee.

AX: Were you also involved in community activism prior to this?

WHANG: Yes. Doing things within the Korean community. We were working with Korean immigrants, teaching English, a lot of community work.

AX: Was it usual at that time for Asian-Americans, regardless of origin, to come together in common cause?

YAMADA: No, it wasn’t common at all. Most [other] Asian cultures hate Japanese for a reason, and that has carried over into being in the United States. So, there hasn’t been any number of incidents and events and movements where people [of different Asian backgrounds] have worked together. So, this really was the first. And it was not just different Asian nationalities, but also age, also newcomers and people that were born here. So, that whole spectrum of diversity really came together for Chol Soo.

WHANG: Before this started, the Korean-American community was a very young community. And we’re not at all politically involved in the sense of being active and fighting against injustice, but certainly felt a lot of discrimination, racism, injustice, but we didn’t have any models growing up about people fighting. My parents are second generation. They grew up in this country, and faced a lot of racism and discrimination, but just kept their nose under the radar, and didn’t get involved.

It wasn’t until I think our generation that [Korean-Americans were] influenced by the civil rights movement, Reading Malcolm X, I think that was my first awakening. And so, when we got involved, a lot of older Koreans – I mean, “older,” I don’t know how much older they are than I am [laughs], but they represented a different segment of the population. They were churchgoing, and they spoke Korean – I don’t speak Korean – and the fact that this was a Korean immigrant, they all could identify. They all had some Chol Soo Lee within them.

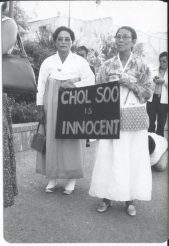

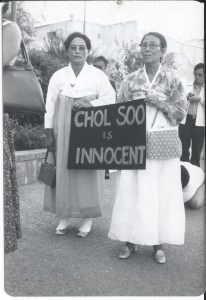

It galvanized people coming together. People wanted to do something. But there was a lot of belief in the system. And one way that it manifested itself was that when we were organizing, some of us were saying, “Freedom for Chol Soo Lee!” We wanted him free, because we understood the criminal justice system. And there was a group of older Koreans, who questioned that slogan. They said, “Free, but – he had a gun, right? We can agree that he didn’t get a fair trial.”

So, there were differences, and so some of the signs that you might see say, “Fair Trial for Chol Soo Lee,” or “Justice for Chol Soo Lee,” but it was different than “Freedom for Chol Soo Lee!” I’m talking about in the beginning. By the time that you met them or talked to them, they were clearly about “Free Chol Soo Lee.”

I think through the whole movement, the Korean community got educated and politicized, and got more understanding about how the system was not working in our favor. When you follow the case, and look at what was going on with the D.A. and the whole justice system, people came to their own conclusions. So, by the time you guys [Ha and Yi] came around, people clearly understood.

YI: The fact that there are these differences and they came together I think just speaks to the solidarity that they were able to put together. Everybody talks about solidarity these days – it’s very catch-phrasey. But they did the work. These are not easy compromises. It was not easy to cross these lines of language, and of culture, and of generation, and national origin, and politics, what have you. And so, I think particularly at the time, not long after the term “Asian-American” was first invented, it wasn’t just solidarity they were fostering. They were crafting and creating the idea of what “Asian-American” could be. And I think there’s a larger lesson today, for not just Asian-Americans, but for everyone.

YAMADA: But this also shows the brilliance of K.W. Lee. Because when he wrote these articles, he wrote very specific details, but to be used to show people what the case is about. And without that in writing, that you could take around to churches and begin to explain such a complicated situation that surrounded [Chol Soo Lee], it wouldn’t have played out that way.

AX: In putting FREE CHOL SOO LEE together, how did you decide who you wanted to talk to, and how did you find archival footage and recordings?

YI: A lot of doors were opened by K.W. Lee, by Julie’s relationship with him for so long, and that led to a lot of connecting to people who were connected to the movement, like Gail and Ranko.

As far as the archival [material] goes, it wasn’t an institutional or an official archive, it was something that was harbored by individuals of the community, and that, over the process of getting to know people, we found and formed what we came to call an underground archive of material about Chol Soo Lee. I think it just says a lot that it was largely Asian-Americans who hung onto this material, and were able to preserve and make this history, because archival footage doesn’t just archive itself. Someone needs to make that decision. [To Ha] Do you want to speak to how we chose that?

HA: It was difficult to narrow down the list of activists that we interviewed on camera, because there were so many incredible individuals who took part in this movement. But we knew we couldn’t interview everyone, and so we focused on certain key people who we thought could help us just flesh out what this movement was like, in the spirit of it, and it’s worth mentioning that it was not only younger activists [laughs], in their twenties or college-age, but also, when you think about who started the movement, K.W. Lee, a man named Jay Yoo, who passed away recently, he’s in the film, as well as Grace Kim, and these were middle-aged Korean immigrants, and they’re the ones who actually first decided to start a defense committee for Chol Soo Lee.

That’s maybe not the picture of activists that you think about, but it was just that incredible alliance of them, and then young people, young Asian-American radicals, many of them, along with churchgoing grandmothers [laughs] that would show up at these courthouse protests, fighting for justice for Chol Soo Lee. It was a movement I don’t think anyone could have ever imagined in this country.

With Ranko Yamada, she knew Chol Soo Lee before his wrongful arrest. She had befriended him before that, and when you think about her dedication to this case, from that point on, she was like Chol Soo Lee’s lifeline, before there was any movement. So, we knew she was an essential person that was going to be in our film.

And Gail Whang, oh, my gosh, she led the Bay Area Defense Committee activities, and you see her in a lot of our archival footage, out there, and shouting, and singing protest songs. And so, we knew that she was also going to be a very important character in our film as well.

AX: Did either of you provide archival materials?

YAMADA: Yes. I had boxes and boxes in my attic of handwritten notes and documents of meetings, campaigns. Back then, everything was on paper. We wrote endlessly.

WHANG: Same here. I had lots of pictures. Just a week ago, I found slides that were put away in my closet. This is footage that the people involved haven’t seen before, so digging through it was like this incredible treasure hunt, because we’re talking forty-four years ago that I was involved.

AX: Was Chol Soo Lee political before the movement to free him?

YAMADA: Oh, no, not at all.

AX: What was his take on the activism surrounding him?

YAMADA: He may not have known how to respond in different instances, but people that approached him were so supportive of his plight, and wanting to get to know him, and he responded in that way. He was very open about it, and it wasn’t any question at all about what your politics may be. He just greeted and embraced you and was very thankful that you wanted to meet him.

WHANG: He truly helped build the movement. Because if you were moved by K.W.’s article, people wanted to reach out and write to [Chol Soo Lee] in prison. And I’m sure none of us had written letters to somebody who was in prison. And then, to receive a response from him, and just very gracious, and supportive, and so thankful to what we were doing. It was that – boy, talk about jumping on and wanting to get involved, just to have received the letter. And then we went and visited him, and you go to the prison, and sit behind glass, and no contact, and through the phone, and talk. I took my son, and my two nieces. They were thirteen, and eleven, and nine years old, to go visit him. So, yeah, young people – very young people – heard about this as well.

HA: Even though Chol Soo certainly could seem incredibly and genuinely grateful for these strangers coming to his aid, and seeing how incredible that was, he certainly also felt the weight of expectations of this community that believed in him so strongly.

Eugene and I ran across a letter that Chol Soo had written to Ranko at that time, when the movement was really just starting, and he talked about already feeling uneasy about accepting all that help. He had that feeling of, “I can’t believe they’re doing all this for me.” And then he said, “How am I ever going to pay them back? If they do win my freedom …” And so, we see that he did feel that burden, and in a way, he wanted to give everyone the fairytale ending that they had hoped for, but I think in the end, you just see how difficult it is to undo racism, and the damage that racism does. You have this whole movement to free someone, and they accomplish that goal, but then, does that take away any of the lasting damage that it’s done to the person?

AX: He was in jail for quite a long time, and just that, I think, would have damage, as well as the racism. Do you think that the weight of that expectation possibly contributed to his relatively early death?

HA: His death was the result of internal injuries he suffered during the arson. It required surgery, and he declined surgery.

AX: That is, do you think that was one of the reasons he declined the surgery?

YAMADA: Because of the arson, I don’t know how many surgeries he had undergone, but those surgeries were entire, from top to bottom, over and over again. I think he was very tired. And it wasn’t really increasing or improving the quality of his life, to go through these very invasive, serious surgeries.

HA: What Eugene and I came to conclude was that during the many years in witness protection that he spent, and when he was in isolation, and having some time to reflect on everything that had happened in his life, he certainly talked about how it was very difficult, being the symbol of a movement, and that he never asked to be a cause. He just really wanted to be “free from the cage of injustice,” is what he said.

But at the same time, I think he also came to a sort of peace with the fact that he knew how special it was that this group of people decided to dedicate their lives to a stranger. This was a poor Korean immigrant street kid, not a model minority, mind you. He was no angel, as he says in the film. But they thought he was worthy of their time, attention, love, and care, and worthy of a landmark movement.

So, I think Chol Soo Lee knew that, and that’s why he spent the last chapter of his life talking so much about the Free Chol Soo Lee movement, even though it was a burden to him. He wanted to return the humanity that was shown to him, to honor them. And he knew that there could be a meaningful legacy extended, that the case actually inspired a whole generation of young people to become public defenders, and leaders in the community, even, working for the public good, and I think he recognized that it didn’t have to end there. The legacy could continue if people learn this history today.

AX: Chol Soo Lee’s case happened in the ‘70s. Were there things about it that were specific to the ‘70s that couldn’t happen again now, or is it one of those things where, unfortunately, it could?

HA: That’s so hard to answer, but there were certainly circumstances around his arrest and conviction that we could talk about. Even just the lack of bilingual teachers, or counselors, throughout his younger years. Because if you look at his life history, he was sort of ping-ponged from one institution to another, including juvenile hall and mental institutions, as well as prison.

So, you would hope there would have been some changes, but I would say there is still a lot wrong with our criminal justice system. I don’t want to speak to it as an expert, because I’m not, but I don’t think you have to look hard, unfortunately, to find other cases, whether they be of racial profiling or just racial bias in our criminal justice system. I think that’s well documented. The thing is about our film is that you get to see an Asian-American at the center of that racial bias, or racism, in our system. And that’s something you don’t typically see.

YI: I think the only thing I would add to that is, I think, very intentionally, we hope that this sparks and inspires a conversation, both among Asian-Americans and outside of the community as well, about the place that Asian-Americans can have in this conversation as well, because as Julie was saying, these issues still exist, and they just affect us all as Americans, and they continue to.

AX: What would you all most like people to get out of FREE CHOL SOO LEE?

WHANG: When we show the film today, in community events, Asian-Pacific-American film festivals, there’s still, it attracts mainly Asian-Americans, and a lot of younger Asian-Americans, and even older Asian-Americans, who still do not know about Chol Soo Lee. This is within our own community. So, one is to educate our Asian-American communities, but get it out more broadly to mainstream America. Because this is not an isolated case. The legacy that he provides is to educate, and to include. This is part of American history, which we don’t read about in our history textbooks.

YAMADA: Yeah. It should definitely go in the books. It was just such an important event in the lives of all these different Asian-Americans, and it gives non-Asians a view of the Asian community that they would rarely see, unless it was documented in this way.

We’re not two-dimensional [laughs]. There’s great depth and breadth to our community. I think for Asian-Americans who have not seen the movie, I hope that they embrace it, and take it a step further – that if you can identify or feel what transpired in this Chol Soo Lee movement, then it doesn’t take a great leap, then, to understand the outrage and the gatherings and protests with Black Lives Matter, or to understand what happens when migrant families are separated, and children are placed in different detention camps from their parents. Hopefully, it leads to a greater compassion for other people.

WHANG: I think that there are so many lessons to be learned from the grassroots movement that developed, and young Asians are getting involved. They want to come out and, especially around all the anti-Asian hate and the violence that’s going on now, and want to know from the O.G.s [laughs], from those that were involved, and what are some lessons that we can impart to help young people come together and organize.

YI: [laughs] I don’t know if I can add much more to what they’ve said so beautifully. Just to build on what Gail was saying, people are tremendously inspired to know that there is this history of protest, of fight, of resistance in the Asian-American community, and how much that contrasts with what we’ve seen over the past couple of years of these pictures of victimhood, pictures of being assaulted, of being shot, from all the tragedies that we’ve seen.

And so, it’s connecting with our history, and it’s connecting with a different side of ourselves, sure, but it’s something that I think, for Asian-Americans and for all Americans, can really help create this picture of us that is more human, that is more than the two dimensions, like what Ranko was saying, and just fights what’s called “the perpetual foreigner myth,” fights this idea that we don’t belong here, and just demands that, yes, we have a place here, and we belong.

HA: A lot of people, when they watch our film, they see the ending and say, “Wow, what a sad story.” And I often want to tell them, “Yes, it’s true, the Chol Soo Lee story in many ways is very sad, and there’s nothing we can do to change what happened in his life. But what we can do is try to honor his legacy, and extend his legacy today, by telling this story anew.” That’s why Eugene and I made this film.

Because I feel like Chol Soo Lee himself would say this – there are other Chol Soo Lees out there now, today, and they need our time, attention, love, and care, as this movement demonstrated. And so, if we could learn that kind of empathy and compassion, but also realize that, as Eugene was saying, there’s a history of this kind of resistance, to do the impossible, including overturning two murder convictions, which is quite impossible in our American criminal justice system, but they did it. So, we hope that provides that kind of inspiration for people today.

Follow us on Twitter at ASSIGNMENT X

Like us on Facebook at ASSIGNMENT X

Article Source: Assignment X‘

Article: Exclusive Interview: FREE CHOL SOO LEE Filmmakers and activists Julie Ha, Eugene Yi, Gail Whang and Ranko Yamada talk new PBS doc

Related Posts: